Recently, Rick Santorum, Republican party candidate, declared that Puerto Rico would be required to make English its main language if it were to become a state. Just as Santorum’s culture is cemented in his use of English, the Puerto Rican experience has Spanish at its core. The reaction to Santorum’s statements (which he attempted to backtrack on a day later) was to be expected: even Puerto Ricans who speak English well and who I know to be affable people, have little patience for being told what to do. I wouldn’t be surprised if thanks to this latest misstep, that Santorum won’t be able to find a Puerto Rican shopowner or driver, doctor or Congress member, who will agree to address him in English from here forward.

I lived in Puerto Rico for five years, in the early 1990’s. Many people had knowledge of English from their schooling, but many did not. And knowledge of English in Puerto Rico is not greater among people who support statehood, either—in fact the best English I have heard in Puerto Rico has been from independentistas—such as the polished English of Rubén Berríos Martínez (listen to his speeches on YouTube!).

Back in the 20th century, the United States imposed English virtually overnight in Puerto Rico’s schools as part of its “acculturation” campaign to make Puerto Ricans more like us, causing much harm to the children of this Spanish speaking island. The policy was also never able to uproot Spanish, and was eventually abandoned. Awareness of this sad historical fact would probably have made Mr. Santorum hold off on his suggestion. So would have knowing that the United States invaded Puerto Rico in 1898, and it has been a touchy subject ever since, as Puerto Rico’s status violates International Law (hence all those status referendums). Consequently, Spanish has enormous psychological importance to this island. Furthermore, Puerto Rico has a not-too-shabby record of contributions to literature, cooking, commerce, drama, engineering and art, all of it made in Spanish, not English.

Even in the 1990’s, the use of Spanish in the United States was rising like a wave off the coast of Rincón. Legislators who should have taken note, and worked to change our education policy to respond to the growth of Spanish preferred to ignore it. Public school education in the U.S. still does not require students to become fluent in a second language as a condition of graduation.

The United States does not have an official language. Nor is any state required to choose a “main” language. This is consistent with the liberties we value. We have the right not only to say what is on our minds, but to say it in the language we wish to. To assert that Puerto Ricans should speak mainly English makes me wonder about whether this candidate would seek to undermine my right to express myself in the United States. If I am working with an immigrant in NYC, can I speak his language? Would Santorum (or other candidates who think like him) get rid of the option to apply for unemployment insurance in Spanish, or Haitian, or Chinese?

Has Santorum no yearning for the exotic? Does he really wish to go to Puerto Rico to sit under a palm tree, look out at the cerulean blue water and Spanish forts, and be addressed only in English? Does he never indulge here in the exotic? In other words, does Rick ever order Chinese take out? Drink a cafe au lait? Eat a taco from a street cart? Or watch the Caribbean immigrants play cricket in a local park? Or watch the Puerto Ricans play dominoes on a summer day? Would he have them all speak English while doing these things to prove their allegiance to the U.S.? We’d do well to loosen up a bit—when we let people be who they are, it gives us permission to be ourselves.

On a related note, it is time to cease telling Americans that they don’t need a second language. English dominance is a lie. Our government needs Arabic speakers, Spanish speakers, Urdu speakers, and Chinese speakers. Business needs bi-lingual people. In the U.S., the population that speaks a language other than English at home has increased steadily for the last three decades. In Queens, over 140 languages are heard daily. Language is a human right; mess with it, and you have what the British did to the Irish. The Irish are still angry.

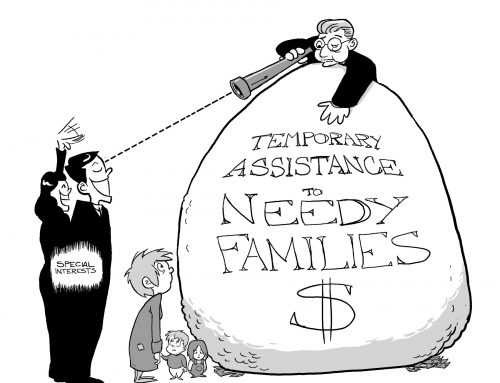

U.S. politicians who publicly profess the superiority of English and imply the inferiority of other languages may seek to preserve opportunity for the privileged classes. No hay problema! After all, the children of the wealthy will still have multiple opportunities after high school to learn other languages. They will serve in the Peace Corps; their parents will send them to Europe; they will sign up for unpaid internships in Asia—while the children of lesser means will not. In this way, rewarding job opportunities are preserved for the children of the wealthy, even as opportunities dwindle for the rest.

Why does Santorum believe that complete ignorance of other languages and cultures enhances patriotism, and “American-ness?” Is it possible that just maybe, the arrogance of suggesting that English need be made the “main” language of anyplace is the same arrogance that irritates, and in some cases enrages, people of other nations? Ay, bendito, as the Puerto Ricans say when witness to acts of God or incredible stupidity.

The author lived in Puerto Rico from 1989-1994 and is a graduate of the Universidad de Puerto Rico.

Leave A Comment