– Photo by John Simoes (jsfotographic.tumblr.com)

January 1941: Franklin Delano Roosevelt talked about the four freedoms, one of them being freedom from want. His position was that no man (or woman) should suffer from a lack of any of the essentials of life. FDR believed this, and he worked to create policies to liberate us from want. Freedom from want, and the right to eat and subsist to a human standard of decency led to the 1935 Social Security Act.

FDR believed in income support, and in the 1930s he decided along with many other Americans that private charity could not effectively protect Americans from poverty, and could not distribute aids like food, heat, and clothing effectively to as many people as needed it. FDR was repulsed by soup kitchens and bread lines and thought them to be shameful evidence of our failure to invest in income distribution policies for our people. If he were alive to know that private charities in the 21st century are once again claiming to be able to aid the growing numbers of struggling Americans with modern day food distribution, he’d outspokenly object to turning back progress on poverty policy by 100 years.

Nothing drives home the need for a new commitment to income distribution in the United States than travelling within the United States. I am in Virginia today, and over the course of the day I have been to Dollar Tree, to Office Depot, to Denny’s Diner, and to a motel. In each of these places, I have met workers. Workers are people. People with dreams and aspirations, working hard in precarious jobs that do not reward them, not spiritually, not financially. A sign outside one of the many restaurants on this strip in Chester, Virginia says “seeking servers, full time, $8 an hour!” That is their exclamation point, not mine. On line to buy some packing tape and other items, and later waiting for a plate of food, I looked at my fellow Americans, unquestionably deserving just by virtue of their humanity, and thought “what will become of us all when these jobs are gone?” Where is the American commitment to decency in one’s standard of living?

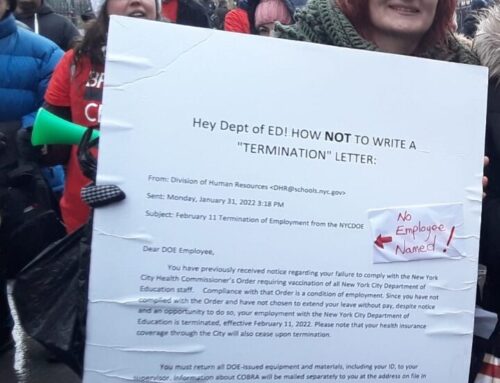

America went down the road of debate on the matter of “private charity” vs. “public policy” in the 1920s and 1930s. Outspoken and knowledgeable activists and policymakers concluded that public policy in the form of income maintenance payments directly to people was superior to doling out soup and bread to lines of humans miles long. This was the brilliant era of children’s rights and mothers’ pensions, The White House Conference on the Care of Children, Harry Hopkins and Roy Lubove. Reformers touted the life saving benefits of income distribution, how mothers’ pensions would reduce the need for impoverished women to be in the labor force, scrabbling for wages in exhausting, low-paid factory, agricultural, or domestic service jobs or, worse still, performing long hours of even more poorly paid drudgery in the home as laundresses or seamstresses.

This was also the watershed era of Social Security. We all love our Social Security, despite its imperfections. Its simplicity, its dignity, its cash in hand. There hasn’t been a better mechanism than cash transfers for solving hunger since–after all, you need money to buy food in America.

America needs a Universal Basic Income. The millions of federal dollars–we’ve been told $27 million–to be cut from emergency food programs, should be cut. Charitable organizations want this funding and tell the public it will harm the poor, but in truth poor people detest emergency food aid, and take it only because they have no choice. But the charitable organizations could rally for income maintenance instead, knowing that it is better for the people the charities serve. That money would go further and do more converted to income maintenance payments, or at a minimum applied to increase Food Stamp monthly allotments.

Not even one hour ago, I met an American who lives in a tent, under a highway overpass. Literate, polite, middle-aged. In the richest nation on earth. Living outside in the 21st century, 100 years after FDR proclaimed our right to freedom from want.

Those who use the stories of economic suffering as a rationale for more “soup kitchens” and “emergency food” miss the larger story–the one about social investment, and the right to freedom from want. The people who are desperate enough to accept “emergency food” need income replacement if they are unpaid caregivers, for example, or if their jobs are being eliminated, not donated (and sometimes expired) food, used clothing, temporary places to sleep. These things undoubtedly do some good on certain days with certain people, but as FDR, Harry Hopkins, and so many social reformers determined a century ago, charitable distribution schemes like bread lines and other food can save only a few for a limited period of time, and collapse under the weight of their own complexity and cost, while the continued spectacle of people homeless, or hat-less, or food-less, rips society apart. Income on the other hand, permits millions of us to save ourselves, and strengthens us all, at the least cost possible.

Leave A Comment